Foundation Figurine of King Ur-Nammu

King Ur-Nammu rebuilt and enlarged one of the most important temples in ancient Mesopotamia - the E-kur of Enlil, the chief god of the pantheon. This figurine, which was buried in a foundation box beneath one of the temple towers, represents the king at the start of the building project - carrying on his head a basket of clay from which would be made the critically important first brick. The foundation deposit also contained an inscribed stone tablet; beads of frit, stone and gold; chips of various stones; and four ancient date pits found perched atop the basket carried by the king.

Funerary Stela

Found in the Ramesseum at Thebes, this painted funerary stela was erected to commemorate the lady Djed-Khonsu-es-ankh. The deceased woman, in a diaphanous white gown, wears a cone of perfumed beeswax and a water lily on her head. She pours a libation over a table of food offerings and raises her hand to greet the seated god Re-Harakhty, a form of the ancient Egyptian sun god. The hieroglyphic signs offer a prayer asking the gods to supply food and drink for the survival of her spirit in the netherworld.

The inscription, a standard offering formula, reads:

An offering which the King gives to Re-Harakhty, the Great God, Lord of Heaven, that he may give invocation-offerings consisting of offerings and food to the Osiris, Lady of the House, the noblewoman, Djed-Khonsu-es-ankh, deceased, daughter of the priest of Amun-Ra, King of the Gods, Master of the Secrets of the Garments of the Gods, Ser- Djehuty.

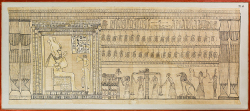

Book of the Dead

The Book of the Dead was a collection of spells, hymns, and prayers intended to secure for the deceased safe passage to and sojourn in the other world. The sections of papyrus on display to the left and right are from one of these long scrolls, which was cut into fifteen sections in modern times.

The illustration to the left shows the judgement of the soul before Osiris, the god of the dead, who determines the deceased's worthiness to enter the next life by assessing his earthly deeds. The heart of Yartiuerow (the deceased) is being weighed in the balance against the feather of the goddess Maat, representing truth and justice. The jackal-god Anubis tips the balance in Yartiuerow's favor while the falcon-headed god Horus looks on and the ibis-headed Thoth, the secretary of the gods, records the favorable verdict. Yartiuerow himself stands on the right, his hands raised in jubilation, accompanied by the goddess Maat. Before him is a monster-part hippopotamus, part crocodile, and part lion- which would have annihilated him had the judgement been unfavorable.

The title of the Book of the Dead and its method of use are stated in the horizontal line at the top of the section exhibited to the right: "Beginning of the spells for going forth by day which raise the glorious ones (i.e., the dead) in the cemetery. To be said on the day of burial of entering in after going forth, by Osiris Yartiuerow, deceased." The vignette below shows part of the funeral procession. The sledge bearing the coffin is drawn by oxen. Two smaller sledges, each drawn by a man, follow. The one behind the coffcin bears the canopic box containing the four jars in which the viscera were preserved. On its lid lies a figure of the mortuary god Anubis in jackal form.

Mud Brick Stamped with Cartouche of Ramses II

Although the ancient Egyptians are best known for their stone monuments, they also used mud bricks extensively for building. This brick, which bears the cartouche of Ramses II, was found within the walls of his great mortuary temple, the Ramesseum, along with many reused bricks stamped with the names of his predecessors.

The bricks were made from river mud and straw, shaped in wooden molds and left to dry in the sun; the cartouche or other inscription was stamped on the brick while it was still damp and soft.

The ancient Egyptian word for brick was "debet," a word that has come into our modern vocabulary through the Spanish as "adobe," meaning sun-dried brick.

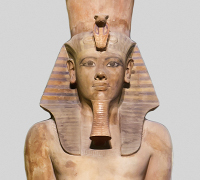

Colossal Statue of Tutankhamun

Oriental Institute archaeologists working at Thebes excavated this statue of King Tutankhamun. It had been usurped by succeeding kings and now bears the name of Horemheb.

Oriental Institute archaeologists working at Thebes excavated this statue of King Tutankhamun. It had been usurped by succeeding kings and now bears the name of Horemheb.

Tutankhamun wears the double crown and the royal nemes headcloth of the pharaohs; a protective cobra goddess (uraeus serpent) rears above his forehead. In his hands the king grasps scroll-like objects thought to be containers for the documents by which the gods affirmed the monarch's right to divine rule. The sword at his waist has a falcon's head, symbol of the god Horus, who was believed to be manifested by the living pharaoh. The small feet at the king's left side were part of a statue of his wife, Ankhesenpaamun, whose figure was more nearly life-sized.

The facial features of this statue strongly resemble other representations of Tutankhamun from his famous tomb, which was discovered relatively intact in the Valley of the Kings.

Coffin of Ipi-Ha-Ishutef

A man named Ipi-ha-ishutef commissioned this coffin and had it decorated with inscriptions and pictures designed to assist him in the afterlife.

The interior of the lid contains spells from the Pyramid Texts to protect the deceased from harm and to facilitate his passage to the netherworld. These texts had been carved on the walls and corridors of royal tombs beginning toward the end of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2755-2213 B.C.). Later, as here, they came to be used by non-royal persons as well and are then known as Coffin Texts.

The eyes painted at the head end of the coffin were positioned opposite the eyes of the deceased as he lay within on his left side. These 'Eyes of Horus' provided him with a magical means of looking out.

Inside the coffin, behind the eyes, is a painted doorway through which the soul of the deceased might pass to visit the outer world. The remainder of the coffin's interior bears representations of items that the deceased had used on earth and would need in the afterlife, such as food, drink, clothing, and weapons, as well as royal insignia, resting mostly on low stands.

This coffin was excavated near the pyramid of King Teti at Saqqara. Ipi-ha-ishutef's title was "Scribe and Overseer of the expedition [or army]."

Human-Headed Winged Bull

This colossal sculpture was one of a pair that guarded the entrance to the throne room of King Sargon II. A protective spirit known as a "lamassu", it is shown as a composite being with the head of a human, the body and ears of a bull, and the wings of a bird. When viewed from the side, the creature appears to be walking; when viewed from the front, to be standing still. Thus it is actually represented with five, rather than four, legs.

This colossal sculpture was one of a pair that guarded the entrance to the throne room of King Sargon II. A protective spirit known as a "lamassu", it is shown as a composite being with the head of a human, the body and ears of a bull, and the wings of a bird. When viewed from the side, the creature appears to be walking; when viewed from the front, to be standing still. Thus it is actually represented with five, rather than four, legs.

Clay Prism of Sennacherib

On the six inscribed sides of this clay prism, King Sennacherib recorded eight military campaigns undertaken against various peoples who refused to submit to Assyrian domination. In all instances, he claims to have been victorious. As part of the third campaign, he beseiged Jerusalem and imposed heavy tribute on Hezekiah, King of Judah-a story also related in the Bible, where Sennacherib is said to have been defeated by "the angel of the Lord," who slew 185,000 Assyrian soldiers (II Kings 18-19).

Clay Tablet and Envelope

Enclosed in its clay envelope, this tablet was stored in a private archive of more than 1,000 texts. The tablet records the outcome of a litigation between two men, both of whom claimed to own the same estate. The judges ruled in favor of the individual who provided written statements attesting to his ownership of the land from residents of nine neighboring towns. Two court officials rolled their cylinder seals across the front of the tablet after it was inscribed, guaranteeing that the information it contained was correct.

Enclosed in its clay envelope, this tablet was stored in a private archive of more than 1,000 texts. The tablet records the outcome of a litigation between two men, both of whom claimed to own the same estate. The judges ruled in favor of the individual who provided written statements attesting to his ownership of the land from residents of nine neighboring towns. Two court officials rolled their cylinder seals across the front of the tablet after it was inscribed, guaranteeing that the information it contained was correct.

Foundation Slab of Xerxes

This stone tablet inscribed with Babylonian cuneiform characters lists the nations under Persian rule shortly after the uprisings that occurred when Xerxes came to the throne. Although the tablet was intended as a foundation deposit to be placed beneath a corner of one of Xerxes' buildings, it apparently was never used. It was found, along with other tablets bearing the same text in Old Persian and Elamite, employed as the facing of a mud brick bench in the garrison quarters at Persepolis.

This stone tablet inscribed with Babylonian cuneiform characters lists the nations under Persian rule shortly after the uprisings that occurred when Xerxes came to the throne. Although the tablet was intended as a foundation deposit to be placed beneath a corner of one of Xerxes' buildings, it apparently was never used. It was found, along with other tablets bearing the same text in Old Persian and Elamite, employed as the facing of a mud brick bench in the garrison quarters at Persepolis.

Fragment of a Scroll

This fragment from a Hebrew manuscript was once part of a library of scrolls hidden in caves near the Dead Sea. The parchment texts, wrapped in linen and stored in pottery jars, were hidden in the first century A.D. and recovered between 1947 and 1956, at which time they became known as the Dead Sea Scrolls. The biblical writings on many of these scrolls are the earliest known Hebrew copies of Old Testament texts. The text on this fragment comes from a non- biblical Essene psalter, similar to the Psalms of the Bible.

Inscribed Ossuary

The name "Yo-ezer the scribe" is inscribed on one end of this ossuary, a repository for bones. Around the end of the 1st century B.C., Jewish burial practices changed from primary burial in wooden coffins to secondary burial in small limestone caskets such as this one. The body seems first to have been buried in a pit until only the bones remained. These were then gathered up and transferred to the ossuary, which was placed in a rock-hewn communal tomb.

This ossuary is decorated with incised geometric designs. The Hebrew inscription on the side reads "Yo-ezer, son of Yehohanan, the scribe."